grief on land

26 June 2023

note on originality & expertise

there's an existent critique of many aspects of the white plant world that i am building on and engaging with here. exactly none of this is my original contribution, not least of which because if there's any knowledge that does not belong or originate with the individual, it's relationship to the (natural) world at large. but most of the critiques i read while writing this piece missed the mark for me in some way or another. this piece is an attempt to fill in those gaps. i'll do my best to provide a list of folks i'm thinking with and alongside, folks whose work i'm indebted to, at the end. also, i intentionally left some homework for myself to do after this piece was finished. i wanted to sort through the emotional-political logics i was seeing for myself before hearing how others, particularly the professional scientific world, were making sense of it all. the resources i have yet to engage with will also be at the bottom. perhaps future me will come back and tend to this piece with their insights.

part I: loss

i've recently gone back to freelancing / part-timing / desperately-cobbling-together land-based work. gardening, farming, landscaping, etc. i joked to one of my coworkers the other day that i should be adding "mugwort murderer" and "precision mulch sweeper" to my resume, to give you a sense of the full miscellany of what i end up doing for pay.

going back to this work has felt full of grief in ways both familiar and unexpected. as i return to spend time with plants and with people working with plants, the confusion and sadness has been rising up again, making itself known. this piece is an attempt to sort through for myself where that grief is felt and what i want to be doing with it.

healing

this form of work has been a mainstay and a fallback for me for about as long as i've had my current form, as long as i've been transitioning, as long as i've been moving away from my natal family and towards a different sort of home and family and way of life.

i think i've always found this work sad, though the contents of that sadness have varied significantly. i started off when my current form was young and terrified; burned out and betrayed by a world i had dreamed of spending my life in, and unsure how i would survive beyond the next day, week, year. i knew very little about plants, but that was fine by the people I worked for; mostly, they needed someone to pull weeds out of their overgrown, poorly tended properties and didn't want to pay much. i needed a job i could pay rent on, and a flexible schedule that i could bail on if i had a bad disability day. so, it worked out. ^

when i started this work, i would pull weeds for about 8 hours a day, listening to podcasts and music and trying to find the resources i needed to change who i was in the world. i was going through an intense healing process at the time, relearning how to be with other people and how to care for myself. in the moment healing felt like long, slow death. i was about 6 months on T, and my clients for the most part decided i was a cis guy, which was the first time I had passed consistently or even been read as GNC. ^ i felt bonedead grief, ache in my chest, terror and anxiety, and all the other early transition symptoms that never quite go away but eventually are made banal -- become colorlessly humorous -- with time and love and knowledge. and through it all, i pulled those weeds, learning each one's name: mugwort, thistle, nettle, chickweed, purslane, creeping charlie. I went home and spent hours researching plants, learning (to my food-insecure, underinsured and sick delight and gratitude) that many of the plants I pulled were edible and medicinal.

i would walk to class and try to spend 5 seconds, 10 seconds just noticing what and who was around me. on the concrete sidewalk of montgomery avenue, listening to the regional rail line roar past a few dozen feet away, i would try to stretch my presence and my gratitude a little further, being in grief with the white pine on the corner, or a blooming flowerbed of yarrow, or a patch of concrete crack purslane. i'd go to lab, get on transit, confront a friend, make dinner alone, and try to maintain some smidge of that presence, some hairfine constancy to keep me. i experimented with the plants i met. i failed to make a white pine hydrosol (it was just water) with a downed bough, learned the hard way that mugwort gives me flashback-nightmares, took skullcap for acute anxiety nearly daily. eventually, it all worked, or close enough. the plants healed me, working with plants healed me, continues to heal me when i do it for work or for sustenance. but the work itself never stopped feeling full of grief.

part II : the aesthetic and the moral

most of the plants that i work with directly as food and as medicine are pulled out of suburban garden beds for mostly aesthetic though purportedly moral reasons.

as a sidebar, it is hard to over-emphasize how much the aesthetic (taste, desire, pleasure, ease) produces the moral in the american suburb. i've got more to say on that subject, but for now i'll constrain myself to commenting on how it affects suburban land management among liberal white people, who are the majority of the people I work for(/with).

the language used to instruct landscapers/gardeners is explicit in making aesthetic preferences (for nativity, for naturalness, for health, for a tasteful and safe amount of wildness) into a holy war against the state of things-as-they-are. i get instructed to "clean" a bed of mugwort, because it is such an "evil, invasive" plant that "wants to take over the world." i'm asked to remove "invasive" plants that "threaten the native landscape," remove "prolific" plants that "reproduce aggressively," and even asked to regulate "abundance" in certain species "threatening endangered populations" of native plants. "Is that a bad plant?" people love to ask.

As you hopefully have picked out, the language people use for common plants is famously xenophobic and eugenicist. If all this sounds straight from original Nazi propaganda, that's because it quite literally is. The Nazis had a native plant movement.^ In fact the first organic farming movement^ was led by Rudolf Steiner, an occultist and possible-Nazi-but-certain-racist-antisemite whose works were influential among the fascist right. The German Nazis and their offshoots and collaborators had all sorts of eco-feminist, queer masculinist, pagan, and cultural heritage programmes and philosophies. Much of what passes for Western/European modern paganism is borrowing from the research and aesthetics of this early reactionary fascism and occultism, not directly from some mythical-yet-easily-accessible-to-modern-subjects pre-capitalist literature. It's history I think many communists and jewish ppl are aware of, but the general green and woo left is woefully ignorant of. but that's again another story.

The fetishism of ecological nativity ("native=good, non-native=bad") obscures and confuses the real crises facing the world as we know it. It creates a simple binary solution to the problem of ecosystem collapse: plants and animals from here are good, diasporic species are bad. Then, it attempts to provide a solution: nuke the diasporic species using whatever strategies you can. It's not the only obfuscating fetishism I want to discuss here, but it's one of the more garishly clothed.

i want to make my way here through, among other things, the framing of the "problem" of the existence of diasporic plants, as a way to get at larger contradictions and confusions around human relationships to the rest of the world. i want to move slowly, take a bit of a winding path, so bear with me if you will. i think a lot of what i want to convey in this piece is the feeling of working in the dirt, not a critique of specific behaviors. so come, wriggle around in the mulch with me for a bit.

a brief note on approach and influence

i'm indebted to jenny liou for the term "diasporic species" as an alternative to "non-native." her piece "am i an invasive species?" is well worth the read and if you've gotten this far, you'd probably really appreciate its insights. go give it a read.

a lot of the critiques of the white eco plant world (permaculture, biodynamic farming, white settler herbalists, etc) focus on its habit of stealing indigenous knowledge^ directly or indirectly and then turning around and profiting off it directly (by selling knowledge) or indirectly (by selling the products of that knowledge applied).

i'm not focusing on extending this critique here because it doesn't feel like a critique i can personally make well, as a white settler with no close ties to indigenous land stewards. generally people getting "who does this thing belong to" info wrong on the internet^ has had pretty terrible repercussions for indigenous communities and particularly indigenous land stewardship.^ and besides -- i'm skeptical of the projects themselves, regardless of the source of parts of their knowledge, and i think it's probably a safe bet that the parts of the white plant world i am skeptical about +/ hostile to did not originate with indigenous knowledge systems, because to me they seem to be coming directly from the racist-imperial-scientific methodology complex i am quite well versed in.

i'm also focusing mostly on plants, which is an artificial and stupid approach to this subject on a "let's write an essay about the ecosystem" level, but is a side effect of where my knowledge is and isn't.

speaking of,

ignorance

you'll notice in the previous section that i said people use eugenicist language for common plants, not invasive ones. that was intentional. many of the white suburbanites i do work for -- some of whom have years of experience in plant based work -- describe any plant that grows well enough or spreads quick enough as "invasive," even plants like poke and monarda and virginia creeper that are not only native to the region but usually regarded as ecologically important species.

the message is clear: nativity is fragile, broken, in need of paternalist protection. if a plant is doing well or adapting to new situations under the conditions of capitalism, that means it is a threat to the truly native plants and ecosystems, which are always vulnerable and never able to fend for themselves. anything flourishing must be a threat to the naturalized order of things; nature itself must be produced in relation to its own (definitely real and not made up) established, prior, and stable order. and of course you've got to get the true native ecosystem the right kind of help -- white, educated help. never mind that many parks full of edible, medicinal, abundant plants are within spitting distance of working class neighborhoods experiencing structural abandonment and accumulation by dispossession who could very much use them. make sure to criminalize foraging. and then make sure the people tending your quaint, toothless impersonation of nativity are educated in the right way to wage war against the undesirables, and above all this means educated in whiteness.

there's another message here too that i want to draw attention to. the plants that are desirable are plants that are easy to control. the plants most likely to get dubbed "native" (therefore morally upright) by my clients are plants like butterfly milkweed, sedum, tiarella -- things that have pretty foliage, pretty blooms, and stay right where you put them without spreading quickly. the plants that fall over (if they're not cut back by humans or grazed by critters), the plants that spread well by seed, the plants that send out runners to different parts of beds -- they pose a threat to human control and curation (not to mention building foundations and concrete paths etc) and are less beloved or even tolerated.

knowledge

this season i'm working for and with people who do know their shit (unlike most of the clients i've done work for the longest). they know their shit much, much better than i do. i bullshat my way into horticulture work; they've mostly done it for years in this exact area, many have professional degrees and certifications.

and yet

every time i work with or for a new set of people i get to learn each person's mythology surrounding nativity and ecology and morality. no two mythologies are alike, and most are somewhat incompatible in the details. unraveling each person's commitments and understanding, just like building any relational knowledgebase, takes time. because of the nature of the work (removing some plants and putting in others) it often feels like the mythology for each person is picked up plant-by-plant. "Do you keep this, or pull it out?" "What's your take on virginia creeper?"

these stories have, i think, an outsized effect on how people manage land in the white plant world. so many people, myself included, have mostly learned their trade by oral knowledge-sharing on-the-job. plant mythologies (like all mythologies) transmit worldviews as much as they transmit the "content" of imparted information. it's these worldviews, communicated through individual stories about plants and humans, that i'm interested in digging into. i'll use a couple cases of my own plant storybindings as an example of what this plant-by-plant, person-by-person mythology looks like.

mythologies

violets

we leave them in if we can get away with it wherever i've worked with ecologically minded people; generally i've heard them referred to as native and important pollinator plants.

in actuality there are many, many different violets, originating from most of the temperate parts of the earth. there are some species whose origin in europe vs n america has been under heavy debate (viola rafinesquei). others have been introduced to the eastern us from europe relatively recently, in the last half century (viola epipsila). there's also viola riviniana, which is sold by nurseries under the name viola labradorica; the former is originally from eurasia and africa, whereas the latter is originally from this continent. all of these species, it bears mentioning, Look Like Violets, and therefore are pretty hard to distinguish between unless you're looking real close and they're in bloom (generally only in spring). violets also hybridize extremely easily, meaning the distinctions between species itself enters into "professional botanist argument" territory.

while i fucking love violets (so sweet! so sexy! we love a resilient demulcent bb!), the violets that grow here certainly don't exclusively originate in this part of the world, though I've mostly heard them spoken of as such.

strawbs

there are many different plants called strawberry. a non-exhaustive list:

garden strawberry (hybrid, fragaria x ananassa)

grown on farms and garden plots and the like. a hybrid (crossed for fruit size and flavor), so its seeds aren't true but its runners are. people love to say this one is european, which it is. that is to say, it was bred in brittany circa 1750 from a variety native to present-day chile (fragaria chiloensis) and a variety native to present day eastern US (fragaria virginiana), varieties that were presumably cultivated and bred by indigenous peoples for thousands of years before bein mashed together. white flowers.

wild strawberry (fragaria virginiana) and wild strawberry (fragaria vesca)

strawberries from around here (so called eastern n. america) that have yummy fruits. white flowers. mostly seen these growing where intentionally planted here in the mid atlantic, though my partner tells me they grow all around in wild parts of upstate ny.

barren strawberry (potentilla sterilis)

is not a real strawberry. originally from europe. not sure if it's around in the US actually, not sure if i've seen this one. does not have noticeable fruit, thus the name. white flowers.

barren strawberry II (waldsteinia fragarioides)

is not a real strawberry. lacks runners. often planted ornamentally. originally from north america. yellow flowers. named after some austrian guy, not walden pond as i originally thought. (if i were a plant and someone named me after walden pond id fuckin riot, tho some hapsburg soldier turned naturalist is not exactly better)

mock strawberry (potentilla indica)

is not a real strawberry. originally from south asia. not very tasty but still edible berry. yellow flowers. grows around here really prolifically -- really likes a good stale mulched bed or lawn in my experience. originally brought here as a medicinal and ornamental.^ famously a "lawn pest" according to the lawn industry.

statement from the missouri dept of conservation^ on this plant, emphasis mine:

A line is crossed when introduced plants move into wild areas and threaten to outcompete native plants, which are the rightful heirs of the territory they grow upon. This plant is invasive in many locations across America.

so, there are things in the rose family, that vaguely look like strawberries, that are originally from all sorts of places, many of which crop up in lawns and yards and gardens around these parts, and all of which look fairly similar on first sight. ^

on one of the teams I'm working on right now, volunteer plants^ we see that look like a strawberry are considered beneficial to pollinators/insects and left in beds when we find them and can get away with it. on another team i'm working on, we plant wild strawberries with white flowers, but pull all the mock strawberries with yellow flowers as they're considered invasive.

these plants are hard to tell apart in many stages of growth. even the most obvious difference, flower color, is not helpful in determining nativity; there are from-here strawbish things with yellow flowers, and diasporic strawbish things with white flowers. the cultivated/garden strawberry itself is a technology native to this continent, before its pit stop in europe.

moreover, i couldn't really find any research on whether the mock strawberry i think i've been mostly seeing (potentilla indica) is harmful to anything other than the monoculture lawn aesthetic. nor can i find much information on how it integrates with local ecosystems, other than its frequent appearance on 'noxious pests' lists.

i see it listed as "birds eat it but don't prefer it" on a couple lists, but I also see that it's theorized to have entered the state of Utah via the robin shit dispersal method. this doesn't match up. if robins will eat it and shit it out in quantities large enough to make researchers hypothesize that that was the main way it recently started cropping up in Utah, clearly robins are "preferring" it under current conditions.^

i see many places listing various diasporic potentilla species as "early colonizers of disturbed systems", which is code for "does really well on land that has been fucked by industry halfway to hell and where nothing else can grow," which is consistent with my experience of where I've seen it cropping up. But "does well on fucked land" is a distinct and different ecosystem function from "does really well in mostly undisturbed, less-industrially-fucked, established ecosystems and crowds the species there out." Plants that do well on fucked land are often soil remediators, healing the soil so that a wider variety plants are able to grow in it. They're also often early-succession plants, meaning their dominance within the first few years of presence/remediation often gives way to integration with a larger variety of plants once soil/air quality conditions have changed. It's a lot harder/rarer for a newly introduced plant to dominate a mature ecosystem; possible, but rare in comparison to introduced plants cropping up in areas that have seen the introduction of other "things" (heavy metals, exhaust fumes, etc) as well.

i also see many places saying various diasporic potentilla species are a threat to livestock; if a grazing area becomes dominated by the less/non-edible potentillas, livestock capacity and wellbeing is impacted.^ it's my understanding that cows eating too much of less-edible species and making themselves sick is largely a side effect of fenced-in grazing areas where there's a finite quantity of plant matter available and so more of a less-edible plant means less of the more-edible ones, thus lowering the productivity of the land. unfenced cattle (cattle are, of course, not a native species) do not have as much of an issue, because they can simply range out further to get their nutritional needs met. but again, "makes industrial farmers unable to tend livestock for profit in enclosures" is a far cry from "damaging native ecosystems and/or biodiversity." and potentilla indica is not one of the species mentioned as dangerous to livestock anyway.

so, I really couldn't find much actual specific information on the impact any potentilla had on wildlife or plant communities besides the suburban lawn or the enclosed cattle ecosystems, or potentially the american robin.

applied mythologies

so you've heard my stories of violets and (many) strawbs. any other plant person would likely have another set of stories. ask two different plant people about a few different plants and you're likely to get differing information as to harm, benefit, nativity, desirability, best time to prune, etc. look it up online, you'll see even more information. all of it with intense moral stakes over being a "good" steward or tender of land, which of course are all tied up in aesthetics (looking like a good tender of land, tending land that looks well kept). most of this information is contradictory, often self-contradictory, even/especially when it's coming from invasion biologists and university ag departments and other professional plant people.

i'd like to take a moment, step back from the actual specific plants themselves, and walk through what it takes to have a cultivated garden or stand of land look "well-kept" in a "native plants" or "permaculture" way, under current conditions.^ I'll mostly be discussing this in the context of "amount of land one person could potentially own and want tended," whether that's a tiny rowhome front bed or dozens of acres in the suburbs or country. but the implications of the amount of labor^ required have direct implications on broader land and ecosystem "management" policies and strategies.

nativity

The concept of a plant being "native" to anywhere is not stable. In a settler colonial context, it's usually taken to mean "before white people arrived and started fucking shit up." But plant species migrate over time; native peoples have traded and bred plants intentionally across massive trade routes from the dawn of history to the present day; climate catastrophe has struck before and changed the ecosystem overnight. Even if you set an arbitrary date (say. . . 1492), and decide before that date plants living there were native and after they're non native, what about the plants that were in the process of moving into new areas at that point? How do you define "new" and "areas"? What about the plants that would have made their way over to new spots eventually due to the migration of other species, but were accelerated in their journeys by globalizing trade?

Already we've got problems; determining ~true nativity~ is a fool's errand. But if you do manage to decide on a metric by which things are native or not, the question then becomes which species are "model" migrants and which ones are "harmful" migrants. ^ The native plant movement generally desires the ecosystem that existed in whatever place before the changes associated with global, industrial capitalism-colonialism took place. Their rationality as to why these plants are desirable is generally that they comprise a whole ecosystem. Because these beings evolved together for thousands of years, they help stabilize the conditions for life on earth and mitigate some of the worst effects of industrial extraction.

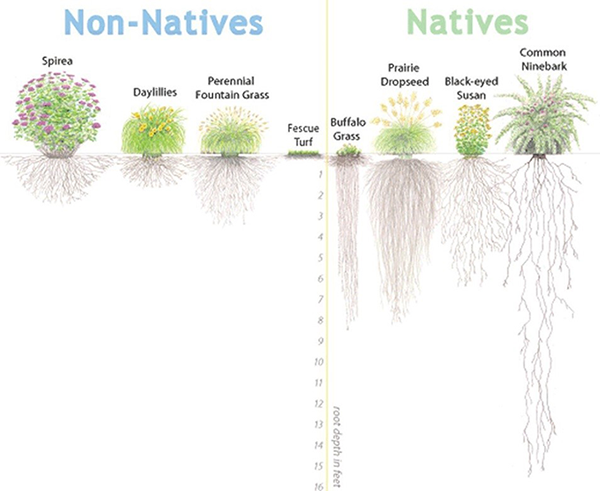

There's some rationale to this. If a plant has hung out in a desert for 3,000 years, it probably has some drought tolerance mechanisms figured out; a water-loving annual in someone's front garden bed does not.

Aand there's also some problems with this theory. Namely: why are diasporic plants thriving in places where native plants are supposedly evolved perfectly for? There are many answers to this question that all boil down to the growing conditions have changed. Plants which are labeled "highly invasive" often do very well in areas where almost all other plants struggle to grow. And "areas where almost all other plants struggle to grow" describes increasing amounts of the landmass of the world. This land has soil full of heavy metals; there are exhaust fumes; the soil has been disturbed or tilled; garbage has been mixed in or dumped on top; there's contamination from various industrial processes, including heavy metals and herbicides and pesticides and debris; species that were in relationship to these plants no longer exist, and new species (including diseases) that thrive under the new conditions have grown up in their place; the n. american deer population explosion makes getting most plants established quite difficult without a deer fence +/ cages due to browsing (eating the plant); the heating of the earth; in other words, the massive ecosystem changes that have happened to the earth as a result of capitalism.

I'd like to quote an essay I read while writing this piece at length, because it fucks and says it better than I can. In "The Discord of Invasion Ecology," author Calyx is talking about the effect of diasporic honeysuckle species on this continent:

The sale of non-native Lonicera species were banned in 25 states after they were deemed invasive by the USDA. In 2011, the University of Pennsylvania conducted a study illustrating that non-native honeysuckles were a key factor in supporting communities of native bird populations and biodiversity, which ironically, as it turns out, was the original purpose for why the honeysuckle species were introduced into the area in the beginning. There are numerous studies that indicate that non-native species provide habitat and food for wild birds. In some cases, the removal of non-native species has caused bird populations to plummet because of the loss of nesting sites. Climate change is altering the timing of migratory birds, causing them to interact with more northern regions later into the season. Many non-native species fruit later in the season than native species, providing food in areas that would otherwise be slim-pickings. Most studies indicate that birds do not discriminate between native or non-native forage options. Many species deemed invasive are highly problematic due to their dispersal by birds, so to suggest they are not a wildlife food source is contradictory. Multiflora rose, non-native Honeysuckles, Autumn olive, Chinese privet, Oriental bittersweet, Porcelainberry, English Ivy, and Callery pear are known for being favored by the birds and thus dispersed widely.

There is also the concern also that non-native fruits frequented by birds are much higher in carbohydrates and contain far less fat compared to native fruits. It is potentially of concern to see such a rapid shift in macronutrient selection, and it is unclear how this will effect the vitality of birds in the near future. There is evidence, however, that migratory birds increase their fat reserves more quickly by feeding on carbs than they do by feeding in fats. It is possible that these birds will quickly adapt to their new diets. And make no mistake- this is their new diet, because even if we increase the abundance of native species, if they aren't fruiting late enough into the season, the birds will be looking for food elsewhere. Increasing temperatures may extend the fruiting period of some native species, but no amount of climate change will change the photoperiod that affects phenology. It is possible that in an effort to protect wild birds by eradicating non-natives, we are eliminating the food sources they need to adapt to their new migratory patterns. It is also important that we stop repeating the fallacy that invasive species are the reason why native species are in decline. Keeping in mind that it is habitat loss, not invasive species, that is the greatest threat to biodiversity, but more importantly is that in most cases it is habitat loss that is enabling invasive species to take hold and thrive. Many of the same factors contributing to habitat loss are also contributing to climate change.^

Really you should just go read the whole post. But what Calyx is getting at is that not only is non-native/native a false binary, the desire to distinguish between the two itself in terms of harm/help to ecosystem stability or biodiversity doesn't necessarily make sense historically, let alone on an ecological scale.

Okay, so we're not sure which species are "from here." Nor are we sure that those ("native") species will do well under the current conditions that the diasporic plants are thriving in. Nor do we really understand the long-scale implications of them being here. But! I want my gddm tree of heaven gone! and the lantern flies with it!

so, what would it take to get them gone?

Most of the plants that are thriving in impossibly damaged ecosystems are tough. The only ways to effectively remove diasporic species altogether and replace them with other, currently less prolific species are expending an incredible amount of manual labor for a very small amount of reward, using a ton of glyphosate (roundup), or using industrial tractors in an attempt to do a "scorched earth" strat and plant into freshly tilled soil. None of these, in my experience, are very practical or economically feasible for anything bigger than a large garden bed in the current economic reality. Let's take them one-by-one.

manually

Manually removing things and putting something else in their place that has half a chance of success takes an incredible amount of labor and upkeep. Even in small garden beds on small properties (quarter acre or less), you're probably looking at weekly maintenance for the first season. Scaled up, for properties larger than an acre or so (generous estimates here), you'd need a whole team of workers working part to full time during the growing season. For smaller organizations with more grassroots budgets, or for organizations such as landscaping businesses operating under market constraints, doing stuff purely via manual labor is largely financially unviable due to the amount of paid labor necessary.

While many private individuals are willing to fund some part time work, fewer are willing/able to fund a full-time team of staff due to the amount of money and organizational overhead involved. There are certainly huge philanthropic grants +/ public money going to multi-million (billion?) dollar conservation projects that could afford to choose manual labor over other strats. ^ But uhhhhh, philanthropy money and public money only come from one place under capitalism, and that's the exploitation of the earth and the species that live on it. Essentially decimating one part of the earth to put in a vanity project in another area. A vanity project that also conveniently serves as PR and coverup for the massive exploitation necessary to fund it, and serves to deflate activism against that exploitation. ^ Not exactly a solution.^

friendship ended with manual labor now glyphosate is my

What about herbicides? It's a hell of a lot more feasible to mass kill unwanted plants with roundup (monsanto-branded glyphosate) and other herbicides than it is to manually pull them. What would take weeks of work for a large crew to do by hand can be done in a day or two using glyphosate. The problem, of course, is that roundup is bad for the ecosystems it's used to manage and the people who manage it alike. Herbicide companies are busy pumping out evidence that glyphosate is nothing to worry about. They're also busy funding the native plant industry, because one of the only ways to scalably introduce native plants is to nuke the diasporic species with glyphosate. Damages to soil health, pollinator and animal health, and laborers' health aside, unwanted plants are also developing resistance to glyphosate, requiring more and more production and application of an incredibly damaging-to-produce and damaging-to-apply substance. Not to mention that the damage to the broader ecosystem by production and application of herbicides makes the conditions even more hospitable to prolific diasporic plants.

there's a certain irony in it all. when i started working on an organic farm full-time, it wasn't even out of a desire to escape capitalism,^ it was out of a desire to learn how to grow food outside of industrial ag. ^ what i actually learned was that small/organic/natural farms are just as reliant on industrialization, and especially the petrochemical industry, as conventional farms. they need cheap quick mulch (plastic and compostable plastic), seed trays (plastic), tractors (burn gas/diesel), hand tools (plastic&metal), rain gear (acrylic), greenhouse materials (plastic/vinyl), market displays (plastic bags for lettuce) etc etc. the pesticides that make organic farming for a surplus aka for market even possible (BT, spinosad, etc) are industrially produced. even soil testing is sent off to a lab. there's a reason it took to the late 20th century in the US specifically for organic/small farming to take off as financially viable,^ and it's because it's (shocker) just as reliant on the technological advancements and beholden to the markets of capitalism as conventional ag. the only difference is the consumer class, as natural-grown food is almost universally a luxury good.

this same bargain with industry appears in the natural landscaping world. people who would fight (okay, i mean i hope they would) if a factory making glyphosate were stationed down the street next to their water supply are happy to use it as consumers to create their little utopias. roundup, the Monsanto brand of glyphosate, is supposedly manufactured in just two factories in the US. one of them is in Luling, Louisiana, in the middle of what is called Cancer Alley due to the density of chemical plants in the corridor pumping out carcinogenics into the air/soil/water. most of the residents of the most polluted sections of cancer alley are black +/ poor people who can't afford to sell their houses and move away because nobody will buy a house built in a hazardous area. there are many new petrochemical plants being built in cancer alley as this piece is being written, despite massive organizing efforts by the people who live there to fight them. ^

the main problem, of course, is still scale. more diasporic species removal = more need for roundup = more production of roundup = more areas that only hardy diasporic species can survive in. monsanto cracked this all the way back in the 90s when it started massively funding native plant conferences. the rest of the herbicide industry and conventional ag industry followed suit.^

Regardless of the harm or lack thereof of roundup application, the harm of producing it continues to be felt.

yea okay that doesn't sound great.....how bout we rip it all out

Okay, so what about razed earth? Cut everything down, pull em out with a massive tractor, till the whole zone and start anew. This is a more expensive option than roundup but probably less expensive than manual labor; you've gotta rent the equipment but it's a hell of a lot quicker to till an acre than it is to manually weed it. probably you could do something bonkers and rig your truck up to remove stumps or something cool like that idk. Even if you find a sexy hack, the problem with this solution is that so-called invasives thrive in disturbed soil. As with roundup, by razing everything to the earth and then zhushing it all around for good measure, you are essentially creating the perfect conditions for plants that thrive in industrial conditions, not plants that thrive(d) under noncapitalist conditions. Your plot may look delightful the first day after planting, but is unlikely to remain that way without significant amounts of manual labor +/ herbicide application.

dont ask me how but it's been done

Alright fine. So you managed to get some plants established via one of the aforementioned methods. Now what?

It's time to meet the neighbors, of course! Because the property line is a human concept that seed dispersal and root systems don't respect, you're looking at a ton of upkeep even if you exhaust the seedbank and rhizomes of the property you're on (which will certainly take a fucking while.) Heaven forbid there's a fenceline; there's a little set of plants I like to call "the fence ecosystem" that will be an eternal timesink. It's worth noting that most seeded meadows and other wilder plantings kinda look like shit for the first few years they're coming in; if the landowner doesn't fire you about this, the neighbors might not be too happy. Especially if your seeds start making their way over to their pristinely mulched beds. But even if you've got land galore and chill neighbors, you'll definitely meet the deer that are so very grateful for their new snacks, and the birds distributing diasporic plant seeds right back into your beautiful new beds, and the paper mulberry and ailanthus trees your neighbor chopped down last week and swore they fckin killed for sure this time (and did not).

And of course -- unless you want to start anew, your options for diasporic species control are now manual labor or selective roundup. If the neighbor's mugwort stand or phragmites stand or heAven forbid goutweed (perish the thought!) starts coming over your way, you're looking at a ton of fidgety weeding +/ roundup application to keep it at bay.

the "problem" is ongoing, too

Worth noting that species are becoming diasporic and cropping up on this continent all the time;

it didn't end in 1990 or whatever year "we" supposedly discovered the pristine purity and beauty moral importance of native species. Diasporic species got here and continue to get here a few different

ways. Either they were planted for ornamental/medicinal/desirable properties by humans; they were brought

here accidentally by humans as seeds/root fragments via international trade (ship/train/boat/plane);

other species like birds brought them here as a result of changes in population/migration; or the government

introduced them in an attempt to control various issues (eg erosion) or other diasporic species. none

of the aforementioned methods of migration have stopped or slowed; new species will continue cropping

up and presenting unique challenges to cultivated and wild spaces.

so

If all this sounds like a really fantastic model for ensuring job security and client retention, you've figured out how native landscaping operates; it's a lot of billable work to try and establish these sorts of plantings. Perhaps contrary to the impression I'm giving here, it's not that creating these plant communities is impossible. It's very doable; it just requires the introduction of lots of raw inputs (plugs, seeds, soil additives) and a heavy amount of labor to keep intact. it's a strat that reaches its limit in the suburban meadow in terms of practicality.

and that's the thing, right? it's not scalable. if the suburban meadow is about as grand of a scheme as can be reasonably executed with these tools, it's not really a viable strategy in terms of ecological change. putting enough of the land in the US into cultivation to have an actual impact on the proliferation of diasporic species would probably require the labor and efforts of a significant portion of the population.^ it goes w/out saying capitalism can't sustain that in the US because it does not produce value (money). without an actual impact, it's essentially a visual deflection, a comforting sleight of hand. look here, not there. look at this beautiful "native" pollinator garden, not at the people tending it who can barely afford to eat. look at this little wetland rain garden that's helping with drainage and habitat, not at the ghost swamps^ surrounding the factory where the glyphosate gets produced.

so after all this. why do we even want them gone? why are people, including/specifically left people, fighting this hard to try and turn back the natural world's response to global capitalism?

the easy answer, i think, has already been given. "we" want them gone as a byproduct of the interests of big ag and industry, managed through the state and university research depts, as the impacts of many diasporic plants to industrial ag can be ruinous. "we" want them gone as a result of the interests of herbicide and pesticide industries, which have poured much of the funding into native plant conferences and invasion biology research since its takeoff in the 90s. look here, not there. eradicate this plant, not the conditions of its being there in the first place.

the above explanation isn't where i'm landing, to be clear. but i think it's part of the answer, so i'm going to slow down a bit to make the stakes a little more explicit.

case study time: the spotted lantern fly

the spotted lantern fly is a planthopper indigenous to parts of eastern asia (china, vietnam). they started showing up in the area i currently live in during the summer of 2020, and though i was not here at the time, i heard it was the talk of the town that year. there are wild pictures of them blanketing trees, porches covered in them, etc etc from around this time.

they feed pretty indiscriminantly on woody host plants, sucking out juices (which can be harmful to the host plant) and excreting honeydew, which can cause sooty mold (also potentially harmful to the host plant). because the slf is not a picky eater, having a significant number of them thriving in a small area poses a risk to industrialized agriculture (especially vineyards) and, of course, ornamental plants. sooty moldy plants aren't a good look.

the PA state department has responded accordingly to these threats. here's their website on the SLF:

The Spotted Lanternfly or SLF, Lycorma delicatula (White), is an invasive planthopper native to Asia first discovered in PA in Berks County in 2014.

SLF feeds on sap from a myriad of plants but has a strong preference for plants important to PA's economy including grapevines, maples, black walnut, birch and willow. SLF's feeding damage stresses plants which can decrease their health and in some cases cause death.

It's not just our plants at risk, it's our economy.

The SLF can impact the viticulture (grape), fruit tree, plant nursery and timber industries, which contribute billions of dollars each year to PA's economy. A 2019 economic impact study estimates that, uncontrolled, this insect could cost the state $324 million annually and more than 2,800 jobs.

...

Report SLF sightings: 1-888-4BAD-FLY^

cool haha. 1-800-4BAD-FLY, super chill. soooo it's pretty explicit here why the state wants em dead. no mention at all of ecosystem impact, and mention of native plant communities only insofar as they form a part of pa's vital extraction industries and agriculture.

it's also like, super not true that they have "a strong preference for plants important to PA's economy" lol. they prefer ailanthus or tree of heaven as a host plant, which is also a diasporic species often regarded as a pest, and they feed pretty widely on other species as well. it would be shocking if any animal had a preference for like, solely plants of economic worth? anyway. so that's the pa state department takes

here's penn state (farm) extension's take:

If not contained, spotted lanternfly potentially could drain Pennsylvania’s economy of at least $324 million annually, according to a study carried out by economists at Penn State. The spotted lanternfly uses its piercing-sucking mouthpart to feed on sap from over 70 different plant species. It has a strong preference for economically important plants including grapevines, maple trees, black walnut, birch, willow, and other trees. The feeding damage significantly stresses the plants which can lead to decreased health and potentially death. As SLF feeds, the insect excretes honeydew (a sugary substance) which can attract bees, wasps, and other insects. The honeydew also builds up and promotes the growth for sooty mold (fungi), which can cover the plant, forest understories, patio furniture, cars, and anything else found below SLF feeding.^

guess we know exactly where the state dept got its information and phrasing. again, no mention of ecological impact and a heavy focus on the impacts to industry and leisure (not the patio furniture!). also, this study everyone's citing? on planthoppers' impacts? was done by the economists?

as a result of these very noticeable new bugs combined with the propaganda put out by the government & university ag depts and amplified by local news,^ there's been a relatively widespread understanding that these bugs are "bad" and should be killed on sight. here's a collage i made of a bunch of stickers i found on the internet (mostly on etsy)

yeah.

this isn't to like demonize people stomping on SLFs lol. ive stomped em too. i also don't want the pa economy to collapse due to a very pretty bug that likes to suck juices, though i do sympathize with its proclivities.

just....yeah. i think (white) people see things that someone at a university put out saying "this is how you save the planet" and are like "cool I'm going to take that at face value and produce incredibly kitschy commercial art about it that i sell for a profit, about how much we should be trying to mass kill this species of bug specifically because it ain't from around here and it's threatening my patio furniture and my local wine, in ways kinda resembling the way people make kitschy commerical art about people who aren't from around here that they feel are threatening their local-wine-and-patio-furniture way of life." and that's perhaps not great

ANYWAY. inflammatory anti-wine-mom sentiments aside. . . it's three years later, and while i still see SLFs^ around, I don't see them in nearly the quantities I did in 2021 when I moved up here -- which was significantly less dramatic than 2020 already. the hypotheses i've seen as to why they've been so much less prolific in this area are

- that they've got more natural predators, or rather natural predators have figured out they're good eating^

- there's a local soil bacteria that is possibly toxic to them,^ and/or

- that they're a bit of a traveling species--- in one area one year, off to the next the year after.

either way -- this is so much change in an ecosystem in so little time. within 5yrs they arrived en masse and then the population leveled out. and while they've decreased in southeastern pa, they're being seen in new places every year. the change is ongoing.

there's certainly evidence that they pose threat to commercial industry. but how could you possibly figure out ecosystem impact in as short a time as 5yrs?

the campaigns against SLF are self-consciously posing themselves as specifically a war to save industry and commercial agriculture. but the discourse i've seen anecdotally amongst green libs and lefts has been with the language "invasive species" and "damage to native ecosystems." this is, i think, how this generally works. research gets funded for economists to throw a fuckin fit about xyz diasporic species' threat to $$$. the ag depts and state depts go cwazy with BAD BUG propaganda to try to mitigate this threat, using preexisting cultural narratives about the "evil" of invasive species being impact on "native ecosystems" to do the work of "why is this bad" despite having no such proof. and then people uptake this as the truth of the matter and backfill their own reasoning and assumptions about why something is "bad" if it's been labeled "invasive."

so that's one answer. and it's compelling.

but the answer that it's ~all a big ag conspiracy~ doesn't satisfy me, not fully. it's partly correct; i doubt native restoration would be as big of a thing particularly in the academic world^ without the existence of glyphosate and without monsanto pumping massive amounts of money into research/propaganda regarding native species restoration. but white plant people are like, famously libertarians? they (we) like, really love a conspiracy theory? particularly if big ag and big industry and the government are conspiring against ~nature~?

the demographics are wrong for the above explanation to be the entire picture. the psychology is off for the target demographic buying what big ag is selling hook line and sinker. so here's my preliminary thoughts on why the above can be true and still white environmental types often buy into the importance of mass killing diasporic species.

control, ignorance, knowledge, suffering

ignorance

it's enforced

most white people have no clue what the hell well tended land looks like. i sure as hell don't, and i do this shit for a living. i've seen cultivated land, i've seen pristine gardens and highly productive farms, but that's different from ecologically tended land. the remaining land i've seen has been tended by the national or state park service. national/state parks exist because the government forcibly evacuated these areas of indigenous people and people in general so they could be used for mostly:

- white leisure (this first and foremost)

- fun little experiments with controlling diasporic species with other diasporic species that end up wreaking more economic havoc/quick changes to ecosystems

- managing fire-dependent ecosystems so poorly that half the west now burns down each summer;

- etc etc

we have no clue what we're doing. and that's not a personal failure, it's enforced economically.

economically

in late capitalist countries, time outdoors is far and wide either a luxury or a part of work. there's not really a common lifeway in existence in the US which involves spending a lot of time building relationships with the natural world outside either an agenda (to make a living) or a marked non-agenda (this time is leisure).

as work it is usually very low paid and hazardous. even my work at a "high end" gardening business is seasonal and paid below cost-of-living. and we're the labor aristocracy of the plant world! my guess would be that the vast majority of people who work outdoors / with plants in the US are undocumented and/or paid criminally low wages.^ ag and seasonal workers in the US are excluded from most labor protections including overtime and minimum wage law due to those industries being predominantly Black at the passage of the original Farm Bill and National Labor Relations Act of 1935. for the better part of a century this has helped ensure that the average working conditions are incredibly exploitative and the opportunities for effective legal organizing slim.

in terms of jobs on the more ecological side versus commercial crop production, there are people working in landscaping/farming/nonprofits/other non-higher-ed economies, whose knowledge comes mostly from the internet and hearsay. the plant stories i mention, the mythologies, they get handed down genealogically just like other belief systems. I've picked up my opinions mostly from working under and alongside people and either taking them at their word or doing my own research -- mostly based on how much i liked their politics and trusted their knowledge, lol. this essay so far has largely been focusing on the limits and shortfalls of this sort of knowledgemaking in the industry. it's not deep knowledge, and most of it is picked up as a side effect of trying to make a profit or get the next grant.

the formal ecology world in the academies and institutions, on the other hand, is rife with all the usual problems of bourgeois science: mistaking the symptom for the disease, inability to see beyond a very short time span due to the practicalities of research, funding by extractive industries, abysmal literacy regarding social reality, and often general ignorance of actually tending plants (the job is research, not spending time tending plants).^ the big lists of INVASIVE PLANTS that federal and state governments have are driven by concern for industry (crops, livestock, drainage and pests in cities), not large scale ecosystem knowledge, as is the funding for natural sciences in general. there is a reason the war against diasporic species is framed as a war, framed as a matter of national security, and that's because the National Invasive Species Council is part of the department of the interior. the exact department tasked with the genocide of native peoples over the past couple centuries. none of this is a mistake.^

and then there's leisure. in terms of significant non-work time spent outdoors, i suppose there's the independently wealthy eccentrist or retired permaculture types. but even they have to hire people if they want to scale at all.^ there's herbalists, and indigenous communities that have managed to retain connection and relationship to land and lifeways. (more on this later, because obviously these exceptions largely comprise what embodied knowledge DOES exist.) but you see what i mean-- they're exceptions to the general rule of alienation from surrounding ecosystems. ^

it also bears mentioning that the natural world is largely inaccessible even if you do have the leisure time. what's not enclosed in private property is generally public parks where you're encouraged to "leave no trace," aka "build no relationships and do not see yourself as part of the ecosystem." if they allow camping, it's generally with a 10-30 day time limit so there's no risk of people being able to legally find a semi/permanent place to squat. even if you own half a forest, you don't own the forest across the street. you can trespass relatively freely if you're a white hunter with the time and skills and inclination to do so, but that's less of an option for most other people.

the basis for a real and widespread knowledge, a grounded and relational knowledge, of the natural world we are a part of, and changing and being changed by every moment, does not really exist in the US right now for most people. the arrogance and righteousness of the white plant world is a symptom of this, not its cause.

knowledge

it's just not possible to obtain!

i'm a physics school dropout so take all this with a heavy dose of talking-out-of-ass about field-i'm-not-actually-in. but it seems to me that we do not, in fact, have many sciencey tools at our disposal to determine long-scale, large-scale ecological impact of diasporic species. we have endless data about what's causing the life-on-earth crisis (capitalism) and what its effects are (massive ecological collapse of intact human, plant, critter communities) and what the risks are (annihilation of life on earth). But I don't see how the scientific method -- whose main tools are fucking around, finding out, and seeing if the same results occur from fucking around and finding out a few more times -- could possibly determine the longrange effects of plants and species who have only been on this continent since the 1990s, 1890s, 1790s, especially when so many other drastic changes have happened to the ecosystems in that time.

the world of what gets called western knowledge or science is very comfortable with categorization, with putting knowledge into boxed-and-labeled order. it's even somewhat comfortable with ignorance; today's ~idk~ is tomorrow's grant proposal is next year's publication. but it is very, very bad with the unknowable.

& there is simply no knowing what all this looks like in the long term, on an ecological scale. and that makes categorizing the behavior of other beings as "bad" or "good", "desirable" or "undesirable", "healing" or "harmful," simply impossible.

suffering, or the protestant ethic she strike again

there's a relationship to suffering and hard work that i think plays a part here, though it's not quite as straightforward as some of the other sentiments.

first, there's a commitment to suffering, doing things that seem hard, and defeatism in the us left in general. the left response to "trying to change xyz didn't work" is, IME, often "fucking try harder then." the list of things-that-are-wrong is unimaginably long and urgent, and culturally there's a demand to look like you're doing something.^ there's a sense that "being a good person" is equivalent to "doing hard work and lots of it" that somehow goes largely uncriticized despite being in the encyclopedia under the header "the protestant ethic and the spirit of capitalism" and "bourgeois individualist systems of morality."^

secondly, i think people who go into plant work like doing work for the most part. compared to many desk jobs in the us, working with plants generally requires a ton of hard work. when i worked at a library, i mostly worked around people with a very high tolerance for "do essentially nothing for hours at a time;" in plant world, i mostly work around people with a low tolerance for doing nothing, and i think "having something concrete and attention-consuming to do" is a pretty widespread preference in this field.^

thirdly, you can make a living for yourself doing any sort of work as long as you convince someone to pay you. you can't make a living not doing any work whatsoever for the most part, at least not under a completely dismantled welfare state. nobody pays for no work to occur. there's a real sense that there's a climate crisis on the left, and a desire for people to be doing full-time work that addresses this, and extractive industries and rich individuals ready to improve their PR by funding that work that supposedly addresses the crisis but really does no such thing. work without clear metrics for being "done" (such as endlessly removing diasporic species from the same bed season after season), work whose existence purportedly helps something, work which doesn't threaten any existing land management paradigms, work which increases demand for specific commodities such as glyphosate, gets proliferated.

all of this combines i think to make people predisposed to think that "being good to the earth" involves a shit ton of very difficult manual labor with very little payoff. the desire is to immediately intervene in ways that are absolutely destined to fail; you get the twofold psychosocial benefit of having done something about it, while at the same time not having succeeded. (success, of course, is always a symptom of having sold out to capital.) the idea that we might want to wait and see how ecosystems respond to massive climate change --- might want to look at natural systems and figure out how to shape them and assist their natural mechanisms rather than doing bloody fucking battle with their fundamental workings --- is not attractive under this worldview. humans are assumed to be outside nature and fundamentally opposed to its workings (eg the concept that "humans ARE the virus" to a supposedly pre-existent, natural state of health), forced to battle endlessly and industriously against its idiotic, naiive bumblings. there's a nice thick substrate of protestant ethic and white saviorism here that's perfectly and ironically consistent with the white supremacist, (settler) colonial scientific management system which birthed the white/native plant movement in the first place.

control

i saved this one for last because i think it goes without saying, yeah? if there's one word to summarize the colonio-capitalist worldview regarding the natural world, it's "control." the hegemonic systemic and psychic response to widespread and un"solveable" ignorance and fear of change in the capitalist system is, currently and historically, to try and maintain control at all costs.

there is so much change coming for this world. the climate crisis we are living through is posing an existential threat to the premises and stability of the value-based global economy. when threatened with drastic change to the system your life gains coherency within, it's a pretty typical response IMO to try and control whatever the fuck you think you can. even or especially if those "things" have a life and autonomy outside you, were never within your control to begin with.

it manifests differently in different people, in different lifeways. but i think the need to feel in control of what changes are happening is pretty central to a lot of the ways predominantly white US movements and orgs interact with the world and seek to shape it.

at its center, this assumption is heartbreakingly naiive and anthropocentric, even as it loudly proclaims its selflessness and impartiality. the need to be in control has at its root an assumption that only (white) humans can possess knowledge, and as an extension of this that all real knowledge can be easily understood by (white) humans. believing that humans have to be in control, rather than in community, creates all sorts of ideological contradictions. the concept that other species might also be intelligently responding to climate change, might have any agency of their own in responding to this systemwide crisis, is foreclosed by this assumption. you end up with language that assumes that when humans move species from place to place in order to eat more easily, we're active exploiters of an externalized "nature;"^ whereas when birds move species from place to place in order to eat more easily, they're part of a passive, ignorant, static "nature" which doesn't know what's best for itself. that nature might have a set of intelligences of its own is precluded and scoffed at.

imo, the concept that humans are in control of a passive, receptive nature is not a side issue or a philosophical nitpick or something that can be worked around practically. it's a fundamental misunderstanding of the existential problems that face life right now and what solutions we have to face them. the perception of agential knowledge as passive ignorance, whether that be in the knowledge systems of racialized people or the knowledge systems of feminized humans or the knowledge systems of all other life, is impossible to integrate with a true understanding of the world and humans' place in it.

pt III: grief

when i started writing this piece, i was feeling angry and prickly. there are so many opinions on plants I find moderately xenophobic at best and genocidally eugenicist at worst, as you have hopefully picked up. i encounter many of these opinions daily, with great emotion and moral anxiety underneath them. but after spending more time with this piece, mostly I feel saddened.

most days in the week I get out of bed painfully early and pull out "undesirable" plants and put desirable ones in their place. the categories of desire shift with time and with the client and with the working crew. we all want to be doing whatever we can for this world we're in. and yet, the tools we have for determining what that is, let alone sticking to that knowledge, are so fucking scarce.

and i feel so much grief and twistedness at this reality. i feel so much appreciation for the beautiful, diseased, disordered, damaged, thriving, resourceful, full and surprising life i am able to witness. as i labor on wealthy white people's private estates for barely enough money to feed myself.

buffy soundtrack where do we go from here

I think something I'm worried about in this piece is coming off as a non-interventionist. As the sort of person who either says "nature is self-healing, so we shouldn't intervene," or who says "well, we can't know everything, so the best thing is to do nothing at all." if there is one takeaway i had from reading capital volume one lol, it is that we are a part of the natural world. capitalism is a natural phenomenon. the ways we can fight it, too, are natural, part of the natural world. and those fights generally aren't won in separating ourselves from our communities and contexts and trying to make it all out from a safe distance. all that you touch you change. all that you change changes you. there is no safe "outside" from which to watch the climate catastrophe occur. we are part of the great open wound of industrialization. and we will be part of its self-healing.^

i said this earlier but it's been a long journey thru the diasporic weeds so i'll reiterate: this really isn't a criticism of specific behaviors. i drive to my job in my car guzzling gasoline and while there i mostly, as a coworker put it quite well, "tend to the mausoleum of stolen wealth." while i'm tending the mausoleum(s), i really enjoy getting to work with from-here plants that humans are trying to keep extant despite ecological difficulty. i think it's really amazing that humans have the capacity to try to do such a thing. and i hope we can foster and tend to as much biodiversity as we can. death is inevitable but that doesn't mean we shouldn't fight to save our loved ones. but "keeping seed banks in existence and accessible to humans" is a very different thing than "materially making a difference on an ecological scale;" it's the latter framing, the framing of this work as "tending land ecologically" rather than "mostly just tending white egos" that i'm objecting to.

roots

i was first put onto skepticism about the native plant industry by the plant medicine world, as i think many people have been. plant medicine people have a natural, some might say a structural, interest in finding out which plant species are so abundant that large harvests are safe for the ecosystem, and then figuring out what all the little uses for those plants are.^ compared to biologists or landscapers or farmers, plant medicine people generally appreciate "weeds" and other unwanted plants for each's unique and current use to humans, rather than primarily their impacts on crops or livestock or aesthetics-morality or even ecology. because like, without abundant stands of plants, there IS no plant medicine people. and because of this, there's a general skepticism of saying xyz plant is "bad" or "invasive" versus figuring out why it's growing somewhere and how it can be of medicine to the life it grows around, and vice versa.

this perspective among plant people, a perspective whose insight has been really central to the writing of this piece, generally gets credited as part of indigenous knowledgeways / traditional ecological knowledge. i want to be clear about that the roots of this knowledge system, both in my own work and in the world at large, are found in indigenous / ecologically integrated cultures, not the white, industrialized, professional plant world. but i also wanna be clear that everything i'm wondering about in the rest of this piece is just that -- my own uninformed wonderings, from the perspective of a person involved in the white, professionalized, industrialized plant world. what follows is things i'm wondering about as i do this work day to day, not information that should be relied upon blindly. i particularly don't want to make out my halfassed thoughts on all this to be coming from any storied indigenous tradition rather than me, and my well-storied ass.

close reading

there's so much that plants can tell you if you know how to listen. i used to see this talked about by plant medicine people and my sorta-autistic ass thought they meant like, they were literally getting voices in their head or some such. and i've had experiences sorta like that, and i think some people do communicate with plants in this way. but there's like, tons of more concrete ways plants can communicate if you have the skills to listen.

certain plants, such as pinellia, really like cultivated spaces. they're likely to crop up in horticultural beds that are well-tended, and their appearance tells you a plot has been getting regular attention. other plants, like mugwort, thrive in soil that has been disturbed, then sorta ignored for years; i'll often see stands of mugwort alongside the paths in public parks, for instance. there's japanese knotweed, which flips out under assault and ends up thriving more and more tenaciously the harder you try to kill it to an almost alarming extent (aspirational). yellow dock really likes it kinda gross; i've seen dock looking especially abundant & happy in compost piles, where there's plenty of decaying matter about. blue vervain, a plant whose main indication for use as medicine in humans is "a person who is uptight as shit," often,, kinda looks like shit in the wild; its mildewey half-bloomed state is always a reminder to me to not be so hard on myself, not be so uptight about how i am in the world.

plot and themes

just as the great mix of ethnicities present in the US traces the story of wars and conflict both local to this settler colony and global to its proxy wars and financial imperialism: so too might the presence of massive stands of phragmites and garlic mustard be used to tell us the histories of the land we're on, and signal the qualities and quantities of changes elsewhere. "we are here because you were there."^ i'm thinking about potentilla indica entering the state of Utah via robin shit. thinking about what we can learn about the climate by what seeds the birds are shitting, which we can learn in turn by watching what plants are thriving. thinking about the SLF beginning to be eaten by predators after only a year or so of presence in this part of the world. thinking that SLF that've been feeding on the bitter ailanthus trees are being eaten as well, wondering what that says about the availability of food for birds and bugs. perhaps the birds have developed a taste for bitterness? perhaps they're excited by the new flavors and forms of life around them? perhaps they, too, have been circulating the KILL KILL KILL stickers around their neighborhoods?^ probably, they're just trying to eat. just like us.

if a heavy thistle population is often an indicator of poorly tended or abandoned farmland, so too might the presence of abundant contaminated-soil-tolerant species indicate that an area's soil has been contaminated with heavy metals. the same plants that thrive in contaminated soil are often soil remediators -- through phytostabilization and phytoextraction, they can slowly work to contain or remove contaminants in the soil they are found in. thick thistle monocultures often simply disappear after a few seasons of more attentive farming; i would bet the same would be true for plants like sunchoke and goldenrod and purple loosestrife.

oregon grape is on the united plant savers' "to-watch" list in its native range, which just so happens to be where i grew up. as herbalists get into listserv wars (lol) about how best to harvest from the plant, to both preserve its life energy and get the most potent medicine for the amount of material harvested, the same plant that is at risk in its historical range is considered "wildly invasive" in much of the east coast and europe.^ one reason is that it spreads really well by rhizome; another is that birds seem to love its "grapes" in its new range, and keep distributing its seeds outside the easy reach of park rangers (also lol). one of the interesting opinions on plants i came across while writing this piece was by someone writing all the way back in 1990. this person (David I. Theodoropoulos)^ was suggesting that instead of trying to dig a shit ton of newly introduced diasporic species out of the places where they're currently thriving, we should actually be trying to distribute more species around to places where they might do well. rather than trying desperately to make oregon grape happy solely in its native range, under this formulation, humans would try to find other species from its habitat that might do better in the places oregon grape is now thriving in hopes of preserving these species' existence in a rapidly changing climate. i'll be extremely frank with you--- i super don't have enough ecological knowledge to have a sense of whether this is a great plan or a really fucking terrible one. but what i do know is that i'd literally never heard of this as a potential strategy for responding to the biodiversity crisis, whereas i have heard endlessly about strategies for managing "invasives" that after a few seconds' thought could not possibly scale and probably wouldn't help much even if they could.

lyme disease is on the rise in n. america, a problem which has its roots in the explosion of the tick population; which itself is a symptom of the explosion of the deer population; which is itself a symptom of the decline of large predators on the continent. over the past couple centuries, as these conditions for prolific lyme were coming into their current shape, japanese knotweed has become a common sight on the edges of wetlands and in wooded areas over much of the us. knotweed is many useful things to many species,^ but it has a particular affinity for helping treat lyme disease, an affinity even conventional medicine has taken note of. there's a certain irony and beauty in this symmetry that several herb people i read have noted. it follows the classic plant medicine adage of the cure being found by the disease. often this phrase refers to pairs of plants like poison ivy and jewelweed (whose juices help neutralize the active irritant in poison ivy, urushiol), or stinging nettle and plantain/dock (whose juices help soothe nettle stings) often appearing next to each other in the wild. it's almost a dialectic relationship here between disease, medicine, and cure. there's a symmetry here that is mirrored in so many of the ways the natural world operates, symmetries that get lost in eradication-oriented approaches to disease and disorder and disability.

curiosity and humility

part of the grief i feel doing this work is that even as i try to move away from some of these mythologies' hold on my own understandings, i inescapably continue doing work furthering their hegemony. i spend my days removing death and disease from view, curating and controlling the natural world, holding my tongue as people discuss nativity and desirability. all (capitalist) work is predicated on this split, but land work involves less layers of abstraction to cushion the pain and contradictions. it feels like both a privilege and a burden to be so physically present and witness to this split, inside myself, inside my coworkers, inside the ecosystem itself.

holding this split is where the work is for me right now, i think.

thanks for reading.

~

resources

further resources i have read, in no particular order

- discord of invasion ecology -- calyx

- differential morphology: mock strawberry and wild strawberry - calyx

- am i an invasive species? - jenny liou

- some notes on the mania for native plants in germany - gert groening and joachim wolschke-bulmahn

- natives vs exotics - david i. theodoropoulos

- braiding sweetgrass - robin wall kimmerer

- ghost forest: atlas of a drowning world - anne mcclintock

further resources i have not read/vetted

- rambunctious garden: saving nature in a post-wild world - emma marris

- the new wild - why invasive species will be nature's salvation

- fifty years of invasion ecology: the legacy of charles elton - matthew k. chew and andrew l. hamilton

- invasive species, indigenous stewards, and vulnerability discourse - reo, n.j., whyte, k., ranco, d., brandt, j., blackmer, e., & elliott, b.

reliable online/free resources for plant medicine information because i can't help myself i think you learn as much esp emotionally from forming relationships w plants+critters as u do reading

note i do not necessarily condone authors' politics or takes! you'll note this list is mostly white herbalists from the pre-web-2.0 era. there's a ton out there by bipoc & queer herbalists but much/most of that content is behind web 2.0 walls (eg instagram etc) that makes it a spoons intensive task for me to find the accts let alone find any actual info once i'm there. most of the stuff below is search engine or hyperlink directory based which is personally easier for me to navigate. if you're ISO bipoc +/ gay herbalists to learn from do hmu @ the email in my footer, i do have a list of instagram accts etsy pages etc. i can pass along. ive also been out of the herb world social media game for like 3-4 years so. if you want someone added... just email me...

- queering herbalism (toi scott)

- dandilioness herbals (dana l woodruff)

- herb rally monographs

- a modern herbal (maud grieve)

- sw school of botanical medicine (michael moore)

- herbcraft (jim mcdonald)

- henriette's herbal homepage (henriette kress)

- medical herbalism journal

- northeast school of botanical medicine (7song)

- alleanza verde – green alliance

- radical vitalism (dave meesters and janet kent)

- herbs for mental health (defunct but VITAL resource)

~

^ it worked out ofc because of my whiteness and gender as well. at the time, i thought of my position as quite privileged -- being seen as just some college dude doing college dude work. in retrospect being paid $10/hr to be a joint therapist and weed puller in very hot weather was not under any rubric "privilege." but the ability to make that work financially through student loan debt was, which eventually allowed for me to get jobs in this field that pay slightly closer to living wage.

^ i was a high femme child and land based work is approximately the only time i butch it up

^ some notes on the mania for native plants in germany -

^ in modernity, by white people

^ since it's relevant and i don't want ppl to get it twisted, the working definition of indigeneity i'm using is "peoples who have a particular and persecuted cultural/political/social/national relationship to land and (settler) colonial empire," not "people who have lived in x area for y amount of time."

^ usually these sorts of projects get it wrong by basing their own research on colonial records, and do so because those are easily accessible to white people with no meaningful ties to indigenous communities and knowledge systems. the irony here speaks for itself

^ A good example is the native land map -- when you open it up it even has a disclaimer that